- Home

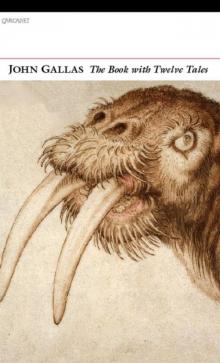

- John Gallas

The Book with Twelve Tales

The Book with Twelve Tales Read online

JOHN GALLAS

The Book with Twelve Tales

Contents

Title Page

Morten Mortenssen the Fat Pig

The Mongolian Economy

Rich

The Ballad of Lucky Razek

The Suspicious Llama

The Tale of Tales

The Monkey’s Dilemma

President Kala and Imi the Poet

Ao the Kiwi

The Tale of Lawrence of Arabia post mortem

The Ferret of Shalott

Rabies!

About the Author

Also by John Gallas from Carcanet

Copyright

Morten Mortenssen the Fat Pig

Morten Mortenssen was a fat pig.

Which was rather the point.

He lived in a paludal paddock

at the back of a cold bungalow

somewhere down the road between

Norre Nebel and Norre Bork,

which was called Sausage Cottage,

where the sun sat in the sky like a frozen backside.

Winter was clangingly long,

like a long piece of frostbitten tin

nailed lengthily over the world,

along which Morten rattled and farted,

sourly surveying the foodless tray of paddock

that was his confines, and his range.

‘This,’ he grunted, ‘is getting on my tits.’

And the icy sky bit the sun tighter and tighter.

Morten blobbed down in his sty,

decorated in a hot, wet cloud of burp.

Straw tickled his testicles. A gleam

of unstrenuous excitement flibbled in his eyes.

His stomach lay like bagpipes in the mud

and hooted complaints and airs of Sir Hunger.

His trotters twitched in a horny not-dance

and a white-meat face watched from the bungalow window.

‘Hawgs,’ said Niels One, ‘can see the wind they reckon.’

He withdrew his pipe and stared at it like it was Philosophy.

‘Plugoles,’ replied Niels Two. He took his face

out of the kitchen window and sat down at the table

and puffed his pipe. ‘If Hawgs cd see the wind’ – puff –

‘sorsages wd be blue.’ He looked long

at the ceiling. ‘Mmmmm,’ replied Niels One.

Morten fluttered his beautiful white eyelashes.

The next day was clangingly long and cold.

The Nielses stamped across the long, tin paddock

wrapped in matching sweaters and beanies

to stare at Morten’s progress. Morten’s eyes narrowed.

He heaved himself into a winningly helpless lump,

his trotters in the air for his Cross, his belly awry.

‘Aaaaagh,’ said Morten. The Nielses looked down,

their pipe-smokes curling past the bum sun.

‘Ooooh aaaagh,’ said Morten, more loudly.

His tongue hung out in a snotty picture of Starving.

‘Mmmmm,’ said the Nielses.

Morten waved a futile trotter, cunningly, he thought,

indicating the frozen, unrootleable bloody earth

and dribbled terrifically. ‘Yum,’ he drooled.

‘Hawg,’ said Niels One, nodding wisely:

at which Morten exposed his unattractive penis for proof.

‘When Hawgs is hungry,’ said Niels One,

pointing his pipe-stem at the straining sun,

‘the moon’ll be a near of corn they reckon

come Lammastide.’ ‘Ducks,’ said Niels Two.

Morten barraged to his feet, impelled by this handy wisdom,

and, in a clicking sort of way, danced out

onto the nailed-tin paddock, where he smacked his trotters

and dropped sad, hot snot onto the icy, bastard world.

By evening, when the stars were stabbing their icepins

through the black fabric of Night, and the deep –

whatever … by then, Morten had his fat head

stuck in a bucket of rotten apples and frozen chips,

baked beans, old cream buns and squashed sprouts,

and was farting happily in the manner of a Melody

while the grass snapped and squidged in frozen horror.

‘Ha easy crunch yum chaw chaw,’ said Morten cleverly.

The Nielses sat in their condensated kitchen,

a hot water bottle on the table for warmth,

and puffed on their pipes. They communicated

by Smoke-Rings: that a Hawg that cannot rootle

because the world is froze is a peevish Hawg,

a scrawny Hawg and, God Help Us, a mean Hawg.

The little sign that said Sausage Cottage rattled,

and the Nielses saw, smokily, a wolf at the door.

Every day from October to March, under the cold-meat sun,

Morten did his fat, The-Earth-Is-Frozen dance,

threatening, like Salome, to disgruntle Certain People

if he did not get what he wanted. The Nielses,

puffing, steaming, smoking and sermonising,

struggled with a traffic jam of plastic buckets

filled with the neighbourhood’s helpful rubbish.

Whereby Niels One developed a hot shiver, and Niels Two a worm.

And Morten Mortenssen burgeoned, flowered and blossomed.

It was nippy and inconvenient to go outside and dance:

but in truth he rather enjoyed hurling his stomach to and fro

and clattering like a submachinegun on the ice.

Unfortunately, May the twenty-seventh was a warm spell.

The paludal paddock softened softeningly

and tasty beech mast and click-beetle grubs

rose to the surface like turds in a puddle,

while the sun rotisseried itself though only at Mark One.

And other nice, green, living things began

to burgeon, flower and blossom. Morten’s eyes narrowed.

He had, in fact, Retired from Rootling, realising that

being Fit was inconsequential and dull compared to

being Fat. He stared at the dripping kitchen window

and fluttered his beautiful white eyelashes.

The testicle-tickling straw begot a gigantic, genial fart,

and the sun set like a half-cooked joint, tied up with fog.

Soon it was Very Late in Spring, which was almost

the season when pigs in Morten’s Land of Pigs

skipped out to fend for themselves. Morten watched crossly

as the neighbours’ fields became dotted with animals

that rootled and snorted for cockchafers and acorns

in the unwillingly reinvigorated grass and brush.

‘Bugger that for a game of soldiers,’ said Morten,

and he fluttered his eyelashes and waited for his bucket.

But one day the Nielses didn’t come.

Morten stuck his snout out into the balmy morning

and dribbled as he inspected the kitchen window.

He tapped his trotter. It went plop-plop in the mud.

He yelped, and lay helplessly in his sty doorway.

He grunted and laid out his extensive stomach.

He staggered along the grass in a fair imitation of faintness

but no one came. The sun lowered itself to watch.

Morten’s pleasant pantomime stopped abruptly.

He crapped overflowingly in the potato beds.

He farted at the sun and burped along the hedge.

He stamped, gruntled and snorted with such venom

; that the merry-making pigs half a mile away lifted up

their marshmallow ears and looked at each other

with big, glassy eyes. He started towards the house.

‘For fuck’s sake,’ he puffed, ‘give me some food!’

Morten mammothed up the front steps, which snapped.

‘Lazy bastards,’ he snorted. The door was shut.

‘Shit,’ he burbled, and butted the plywood panels.

And again. Bomp. The door splintered and fell off its hinges.

‘Right then,’ said Morten, meaning business,

‘where’s those selfish bloody arseholes.’

Well, they weren’t in the kitchen for a start,

though, lit by the enquiring sun, much was.

Flat cans of lager popped listlessly on the table.

Pig magazines limp with condensation on the floor.

Sweaters, socks, beanies and underpants inside out

on the chairs. Charred, greasy pots and pans on the oven.

Shrivelled grilly things under the grill. And

a sink full of fat, Coco-Pops, tobacco-shreds and dishes.

‘Oh yum,’ said Morten, hauling himself up to snortle.

Then he noticed a meandering stream of vomit on the lino.

‘Ahaaa,’ said Morten, and trotted after it, lumberingly.

His stomach bubbled and sucked like an emptying bath.

When he got to the kitchen door, the vomit,

which was pink, runny and almost completely blobless,

became rather bloody. A pair of shat-in

shell-suit pants lay halfway down the hall.

Morten stared at them as he wobbled past,

while the sun rolled round the house, curious too.

Sausage Cottage trembled. Morten hauled himself

to the end of the thin, yellow carpet, where he stopped

to worry the blood, which was now glittered with worms,

with his shiny, pumping snout. ‘Mmmm,’ he said.

His fine sense of smell led him to the bedroom.

He smashed the door down with his cross head.

‘Feed me you bastards!’ he bellowed. Ah –

the Nielses were lying unslumberlikely on the bed.

Morten narrowed his eyes and tapped his trotter.

The window was blinded with tacked-up binbags.

The sun peeped in round the edges with snoopy brilliance.

The Nielses didn’t move. Morten staggered nearer.

The Star Wars sleeping-bags were teeming with worms.

The matching pillowslips looked like blocks of blood.

The Nielses had fallen rather to bits.

‘Selfish piles of shit,’ said Morten. The sun smiled.

Not feeding a fat, lazy pig is hardly sufficient cause

to be eaten alive. But the Nielses were. Though only just.

Morten, infuriated by the interruption in service,

ate the servants. It took him several days,

but had the advantage of never having to move far.

And then he lay down in a pile of bones and teeth

and licked the blood off the bed-linen, and ate the worms.

Which was where, a month later, the police found him.

They were minded, in their nausea, to arrest Morten

and put him on trial for murder. But that seemed silly

in the broad light of day, of which the sun provided plenty.

Repackaging into Meals seemed like a pretty good alternative.

The Universe, especially the Men part of it,

is indefatigably moral, and Morten Mortenssen

could hardly raise himself anymore to be a stud.

The sun dropped onto the plate of the horizon, well done.

The Mongolian Economy

Long ago – achoo! – in Choybalsan

a pretty woman and a handsome man

got married. Everybody was invited,

and everyone declared themselves delighted.

The bride wore everything. They all had tea.

The yurt extension buzzed with bonhomie,

and then they all went home, and it was spring.

I miss Mongolia. The ouzels sing,

the ermine sniff the sky, the aspens shake,

the goats gambol, the corncrakes corn and crake,

the salmon jump, the camels honk – achoo! –

the marmots scamper round like marmots do,

the snowcock squeals and paddles through the sky,

the sturgeon bubbles up, the cedars sigh,

the honeysuckle swirls, the leopards yawn,

and Nature’s children bud and sprout and spawn

till all the world is full of life again:

which also should include the world of Men.

The pretty little yurt stood neat and still

where Hoo (the groom) drove sheep across the hill

and Sim (the bride) made yoghurt in the sun,

which set (the sun): when one by one by one

she lit the candles. Hoo came home. They ate.

The candles sparkled. When the clock said Late

they went to bed. Let’s ride! said Hoo. He put

a Russian condom on and then his foot

against the stirrup of her thigh and whoa!

they cantered off. They crossed the steppes, then slow

along the Gobi, right up Tavanbogdo,

down the beary forest, through the snow,

splashing up the Tuul and past the plains,

chucking off the bridle and the reins

they galloped into yoghurt hell-for-leather

and jumped the Milky Way – achoo! – together.

And when we can afford to have a child

we’ll do it bareback! Sim lay back and smiled.

They blew the candles out and went to sleep.

She dreamed of having twins. He dreamed of sheep.

And summer came like fire. The sick air boiled.

The sheep got Redfly Rot. The yoghurt spoiled.

The pretty little yurt turned brittle-brown.

Hoo rode out across the hill to town

and sold the last spare bags of milk and meat.

He rode back slowly. Withered in the heat,

the yellow plain-grass rattled, scrunched and tore

like paper. Hoo rode on, and wept. He saw

dead marmots in the dust, the little lake

all white and shrunk, the grounded, gasping crake,

the broken thyme, the drooping pines, the sere

and shrivelled poplars, and the trembling deer.

So every day they scrimped and saved: the mutton,

milk and tea; the onions; every button

on their shirts; and every lick of fun.

But when the roiling, red, tendrillious sun

swarmed down behind the plain and darkness dropped

its cool, felt hands across the sky, they stopped

their penny-pinching work, and went to bed.

Hoo took off his hat. Let’s ride! he said.

They lit the candles. Hoo got out his tin

of Russian condoms, put one on and in

and off they went across the shining earth,

galloping for all they both were worth.

Autumn came and went. The plain went blue

and mushed. The days got shorter. Each day, Hoo

rode off to hunt for marmots in the bogs

and Sim sewed little camels, yaks and dogs

on handkerchieves to sell in Choybalsan.

The winter came like death. The sky began

to sweep and swirl, the plain went stiff and black,

the yurt went white, the felt began to crack,

and Sim sat shaking by the feeble fire,

sustained by lard and pregnant with desire.

One morning as she sewed a marmot skin,

her eye fell on the Russian condom tin,

which stood beside the bed, disc

retely veiled

beneath a saddle-cloth. The wild wind wailed

around the yurt. The pallid fire-stove guttered.

Sim got up. Her pretty fingers fluttered

at the cloth. She eyed the tin a minute –

opened it – and – there was nothing in it!

Last night … he had one on … we rode so far …

across the plain … we saw Ulaanbaatar …

the sky was warm … we ate the sugared air …

and sweet, sustaining hope was everywhere …

The black and hungry truth usurped her brain:

the poverty, the childless years, the pain

of Not Enough. The little camel-train,

embroidered through the lashing, endless plain

with needles made of ice and threads of rain

laughed at her defeat. She looked again –

empty.

Right. She took the skinning saw

and went outside. Piled up against the door

were forty frozen marmots shot by Hoo.

She ripped one off. She went inside. She knew

she only had a little time: the day

was almost dark and dead. She sawed away.

Hoo came home with nothing, so they ate

a half-thawed marmot. When the clock said Late

they went to bed. No candles now! He smiled.

Don’t forget we’re saving for a child.

He turned away. He frowned. He found the tin.

She held her breath. He slid his fingers in.

The fire flamed up. Now Hoo believed he’d used

the condoms up last night. He was confused.

Of course he was. Imagine his surprise –

and huge relief – when there before his eyes

(well, somewhere vaguely in the gloomiment)

The Book with Twelve Tales

The Book with Twelve Tales