- Home

- John Gallas

The Book with Twelve Tales Page 2

The Book with Twelve Tales Read online

Page 2

was one more johnny! On and in it went.

Yee-ha! he yelled. They started at a trot.

Now Hoo had planned to say that he had shot

his penis off, or had the flu, or mumps,

or spots, bad breath, the Winter Droop, or lumps

around his testicles: so when the load

of fat, white lies was all unpacked, he rode

with extra enterprise and derring-do,

and Sim increased her saddle-squeaking too.

What with the dark, the wild relief, and not

to mention Love itself, they both forgot

that something wasn’t right. And as they thumped

along the rushing Khalkhin Gol and jumped

on Soyon’s swollen peaks, the marmot’s gut,

intolerably strained and wrong, went phut!

And thus I was conceived – achoo! – and Van.

Crushed by double poverty – a man

who saves a candle cannot save for twins –

we moved to Sukhbaatar. Dad empties bins.

And mum sews dels. And me? Well, I’m a writer.

I live in London now. It’s much politer.

No kids. I went to Sukhbaatar last week

to visit. Their apartment’s pretty bleak.

I got this story. Mum and dad looked old.

But pretty happy. And I got this cold.

Rich

‘With money you can even buy rabbits’ cheese.’ Bosnian proverb

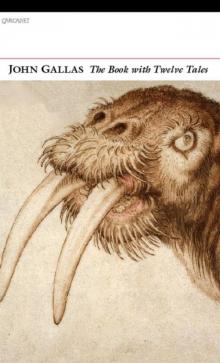

How does a drive of grovelling ermine grab you?

And a front door in the shape of two nubile walrusettes

holding the midnight sun aloft and laughing haha?

And a hall heavier than an ice-floe featuring

wallpaper made out of polar bears, crossed fulmar and

a chandelier of a hundred and sixty decapitated caribou?

And a pinous staircase where wolves in tuxedos

serve gin and Oxburgers beneath the music of

a thousand Red-Throated Loons strung

from the ceiling by silver fishing-lines?

If the answer is Pleasantly, then you might

like the house of Zigismund Walrus,

who is arriving even now

in his enlarged Rolls Royce:

but I rather hope it isn’t.

He is dressed in a Red Fox coat and a top hat

made out of a harbour of Harbour Seals.

His boots are shiny and made out of something else dead.

He is breathing heavily. His breath is fish and clam.

His stained tusks heave in the air with wet yellowness.

His eyes swim in the smoke from a Chinese cigar.

‘Nearly there, my dear,’ he breathes at a shivering

Snow Goose he has pulled half onto his knees.

His erection thumps against her neck.

‘Don’t be frightened.’ The sky is dreadfully white.

The ermine scrabble at the door handles and grovel

in a kind of Mexican Wave. Zigismund Walrus

drags the Snow Goose in through the gaping doors.

The walrusettes laugh haha and No.1 Fox says,

‘Welcome.’ The pinioned Loons shriek.

‘Take the lady to the Very White Room,’

says Zigismund Walrus. Foxes scurry her away.

A feather blows on the marble floor.

It would be wrong to say that it was quickly over.

For the Snow Goose an eternity of anything else

would have been shorter. Zigismund Walrus

did not register – through lack of necessity or the

profession of power – Time. But the foxes knew

that it was about twenty minutes,

according to the Musk-Ox-Head clock.

Zigismund Walrus lies on his white eider cushions

and rings the bell for gin and a fresh cigar.

He is satisfied but unflattered by his performance.

The Snow Goose is put in a bag and drowned.

The eider ducks suffocate in silence.

Zigismund Walrus strokes his whiskers and yawns.

His stomach rises like a Zeppelin.

Availability has made pleasure less exciting.

Frequency has dulled his appetites.

Fear has precluded love, obsequiousness friendship

and luxury discernment. He yawns again

and rings the bell for a gigantic iced bath.

And now Zigismund Walrus is bored.

Everything yields to Wealth, says Alberto Blest Gana.

He was speaking of Chile, but the general rule applies.

The rich man’s wealth is his strong city, says Proverbs 10:15.

To be wealthier or more powerful is not necessarily

to be worthier, says Heloise.

Zigismund Walrus yawns so his tusks tickle the ceiling

and rolls himself out on his Seal Sofa. His stomach

groans a little like an ape lost in the Underground.

‘I WANT RABBITS’ CHEESE!’ he barks.

The foxes mutter, shuffle and enquire:

What why how where.

‘NOOOOOW!’ Zigismund Walrus stands up,

eclipsing the room with fat. The foxes scatter,

dropping blobs of Oxburger and steely drips of gin

from their trays. Zigismund Walrus smiles.

Evening falls like the House of Usher. Unpleasantly.

Domed into their black puffa jackets, the foxes

hiss across the iron pack-ice on a squadron

of dog sledges. Their wraparound dark glasses

reflect a sliding white line that resembles the purity of Maths.

Their revolvers are too cold to touch.

They are headed towards Arctic Rabbittown

to make cheese. Ten sledges of Lady’s Bedstraw

squashed in leather bags slide on behind.

A Lemming Professor of Dairy Studies

from the University of Svalbard,

guarded by foxes with fusils,

hisses along coolly in their midst, crucified to a

handy wooden pallet like a living recipe book.

Arctic Rabbittown is quiet.

Rabbits are lolloping and twitching here and there

amongst the vegetable sheep and tussock.

Some are burping in their holes

or thinking of yesterday in warmish hollows.

The sunlight is mean but not cold.

Rabbit-puppies scramble around in bundles.

Mothers lactate in the buzz of contentment.

Patches of airy snow melt with

the slowness of dying cells.

Everlasting peace is a dream, says Count Helmuth von Moltke.

He goes on to say it is not even a pleasant one,

but the general rule applies.

All we are saying is give peace a chance,

say John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

Peace is in the grave, says Shelley.

Rabbit No. 243 stands up his ears to test

the cold vibrations of morning.

They seem unusual and worrying.

He closes the little lash portcullises of his eyes

and trembles with concentration.

A distant drumming rolls beneath

the chime of his heart. He gasps but does not move.

It is not the clicking groan of shifting ice.

It is not the growl of the sea.

It is not the thrum of evening.

It is not the world turning or

the sun winding its way up the sky.

It is not the grinding of time.

And, being none of these, it is danger.

Rabbit No. 243 propels himself down the hill.

The sky is a grey mist painted yellow.

Zigismud Walrus turns over, steamrollering the softer

wildlife beneath him. Coins fall out of his dressing-gown

and spin on the marble floors. He is sleeping

&nbs

p; a dreamless sleep. Whether this be peace,

lack of imagination, contentment, exhaustion

of various kinds, moral bankruptcy, security,

Heaven or Hell, is debatable. I think perhaps now

Zigismund Walrus’s money is, without being actually spent,

but, nevertheless, as a most powerful Cause,

Making Things Happen, and the Prime Mover,

who does not have the moralities of Free Will

to arbitrate amongst in the acts and minds of creatures

he has animated for his own purposes,

may take a rest from the world,

having set it on its inevitable course.

The horror! The horror! says Mr Kurtz.

Between 11 a.m. and 4 p.m., when the sun escaped

from the sky like an eye wounded by the world,

eleven hundred female rabbits died, and

sixteen hundred puppies. Three hundred male rabbits,

defending one or the other, went the same way.

No foxes were hurt.

Ten gallons of rabbits’ milk was collected.

A huge fire is lit on the ice.

The milk, lying in a vast pan,

begins to smoke a little over the flames.

The foxes, their dark glasses gleaming red,

hurry hither and thither in the milk-fumes

like fireflies around a moonlit lake.

The bags of Lady’s Bedstraw are pitchforked into the smaze.

Huge spoons stir the milk by a rigging of pulleys.

No.1 Fox chews gum and smiles. The great coagulation,

like the wrong answer to some beautiful question,

is hoisted up and dropped into a bowl of sackcloth.

While it drips and drains, the foxes put on their gloves

and shoot the Professor of Dairy Studies

until he drips like a colander. Then he is thrown,

pallet and all, into a hole in the ice.

Two large bubbles burst in the blood-and milk-thickened air.

Snow begins to float across the ruins

of Arctic Rabbittown. The foxes zip up

their puffa jackets. The cheese drips drippingly.

And nothing shall be impossible to you, says Matthew 17:20.

He is speaking of the Faithful, but the general rule applies.

The difficult we do immediately: the impossible takes

a little longer, says Charles Alexandre de Calonne.

When a distinguished but elderly scientist states

that something is possible, he is almost certainly right.

When he states that something is impossible,

he is very probably wrong, says Arthur C. Clarke.

Arctic Rabbittown is palled with snow.

The wet white winding-sheet lays

its freezing antiseptic on the torn and

broken flesh already purpled by the wind.

Darkness draws its curtain on the day.

A few rabbits limp across the freezing hillocks

and lie down alone to be asleep

before the sun returns, and after.

Zigismund Walrus wakes like a towerblock.

Parts of him come on; others linger, then, unwillingly,

light themselves to see the so-called labours of the day.

He bathes his tonnage in blue icecubes. Two vixens

wash his tusks and whiskers with seaweed and giggle

as they loofah his thunderously swaying arse.

He breakfasts on a thousand clams,

dribbling onto a silk serviette. Then he dresses,

like the earth putting on weather.

Zigismud Walrus stares at the perfectly cubed

lumps of Rabbits’ Cheese. ‘Burp!’ he says.

The day looks ravishing outside.

He flaps at the cheese. For a moment

there is nothing there. Then he rallies.

‘NOW,’ he barks, ‘FIND ME

1) THE IMPOSSIBILITY OF REVOLUTION

2) THE GREEN SUPPLY OF CREATION

3) THE FISH OF CONTINUOUS APPETITE

4) THE BELL OR IT MIGHT BE A SPRING OF

IMMORTALITY!’

And the walrusettes on his great front door

laugh haha at the golden morning, whose snowfall,

gorgeously lit, resembles a shower of coins,

a kind of Mineral Abundance. Zigismund Walrus

grunts and glares. The foxes leave to find maps.

For God is a consuming fire, says Hebrews 12:29.

He is not speaking about anything else.

God ordered motion, but ordained no rest, says Henry Vaughan.

I was born on a day God was sick, says César Abraham Vallejo.

The Ballad of Lucky Razek

for Clifford Harper

The morning ached with loveliness,

the city burst with light;

the bombs fell with a gentle hiss,

and all the sky was bright.

Lucky Razek stepped outside

and glittered in the heat.

Then, happily preoccupied,

he hurried down the street.

He passed the Mosque of Two Kazims,

its golden domes on fire;

he pattered down the Street of Dreams

beside the razor-wire.

Today he had to buy a hat.

A bomber pricked the sky.

He passed the smoking Laundromat.

A police car hooted by.

So keep your head, the sparrows sang.

A shout. A crack. A spark.

Electric blue. A whoosh. A bang.

He pattered past the park.

Just keep your head. He wiped his face.

A Happy Birthday Hat.

He reached the Victory Marketplace.

He stopped. He smiled. He spat.

He ordered tea and cigarettes.

The sun was made of gold.

Flies flew round like jewelled jets.

I’m twenty-two years old –

and Lucky! Only God knows why.

And God knows everything.

He sucked his tea. A puff. A cry.

The sugar sparkled. Ping!

A tray of glasses hit the air.

He lit a cigarette.

The pieces plinked down everywhere.

Old men played cards. Not yet.

The Tigris twinkled in the sun.

He clicked his beads and dreamed.

A pod of dust. A powder gun.

He nodded. Someone screamed.

And while he snoozed a Maori made

a man with paua eyes:

two women in Helsinki played

the start of ‘Butterflies’:

a boy in Ougadougou took

a photo of his goat:

a girl in Shanghai dropped a book:

an Inuit fixed his boat:

and someone killed a pig in Perth:

a hare stood up and blinked:

a star was buried in the earth:

a fly became extinct.

And then he woke. The Tigris gleamed,

the golden mosque-tops shone;

the old men smiled, the tea-boy beamed.

The sounds of war were gone.

Lucky Razek crossed the street.

The Headwear Paradise!

Elite – Upbeat – Complete – Discreet –

Your Nice-Price Merchandise!!

He whistled round the ziggurats

of beanies, hood and flaps,

sombreros, headscarves, cowboy hats,

and skulls and baseball caps.

New York Jetz. He smiled. He spat.

And I luv San Francisco.

Then he saw his favourite hat –

Demolition Disco.

‘Try it on,’ the hat-man said.

‘It’s very cheap.’ ‘Okay.’

Happy Birthday. Keep your head.

A thump. A ricochet.

He propped the mirror up. He twirled.

He grinned. He looked like – whack!

A metal breath. The stallcloth swirled.

The mirror-glass went black.

The cap flew off and down he went.

His blood sprayed up the wall.

The money that he never spent

fluttered through the stall.

And all the marketplace was still

and all the world was wrong.

A single burning daffodil.

A patriotic song.

The tea-boy tiptoed through the fire.

The cap was good as new:

hanging on the razor-wire,

electric midnight-blue.

He stopped. ‘A man without a head’ –

and Lucky’s head was gone –

‘Do not require a hat,’ he said.

He smiled and put it on.

And God saw all the bridges break,

the houses all alight

like candles on a birthday cake,

and all the sky was bright.

The Suspicious Llama

for Michael

There is a small Z road

that loops down a hillside

in Bolivia, and then crosses

a small bridge, and comes to an end

beside a shed and

a bucket of geraniums,

which are the end of Bolivia,

which end is followed by

a small lawn and

a small C road

that is the beginning of Brazil

which slides over a plain

into the arms and space of the people.

The shed is a Passport/Visa and

Customs House for travellers

crossing quietly between Bolivia and Brazil,

and outside, sitting on a chair,

is Alberto Alfredo Acomodadizo,

who is an ant-eater.

The day is warm and very quiet.

Alberto’s uniform is carelessly open.

Nothing much passes this way.

Today nothing at all has passed this way.

The Book with Twelve Tales

The Book with Twelve Tales